The collapse of the Liberals’ urban bastions, the ousting of their Queensland strongman, and a fragmented primary vote reshaped Australian politics in May. Together, they amount to a blunt national verdict: “MAGA” style, imported culture wars have no place in Australian politics. Labor emerges with a clear victory but not a free hand, its mandate is constrained by Senate arithmetic and a crossbench alert to overreach. The political map has been redrawn; the rules of the game, less so.

You might think that after three years of electoral exile the Liberal Party would have learned something. It has not. The same people in the same suits delivered the same speeches, this time dressed up with a borrowed set of grievances from another hemisphere. The election of 2025 was less a defeat than an exorcism. Voters did not merely turn away; they bolted the door against the party’s awkward flirtation with Trumpism. “MAGA” rallies and manufactured culture wars may stir applause in Michigan or Missouri. In Melbourne and Mosman they provoked something closer to a national eye-roll.

As the Liberals laboured over their American impersonation, the Teal independents quietly cemented their hold on the party’s once-prized suburbs. Curtin, Mackellar, Wentworth are no longer the jewels in the Liberal crown They are now fortified Teal strongholds, immune to half-hearted siege. What remains is a political map dramatically redrawn, a party visibly unmoored, and a public that has delivered its verdict: Australia is not in the market for imported populism, especially when it arrives second-hand.

Urban collapse, Liberal edition

This was no gentle electoral correction. It was a demolition. In Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide, name any capital frankly, and the Liberals were stripped bare. The party’s once-reliable urban fortresses did not merely wobble; they folded, as if made of wet cardboard. Attempts to bribe voters with cuts to petrol excise, and to rally them with skirmishes in the so-called “woke wars”, met with weary indifference in the inner suburbs. The Coalition’s metropolitan strategy was as relevant to modern city life as a fax machine.

The “Teal” independents not only held their ground but made it toxic for Liberal comebacks. Kate Chaney, Allegra Spender, Zali Steggall, names that now induce a twitch at Liberal headquarters, expanded their margins while party elders muttered about “messaging problems” and “brand damage”. But when the message amounts to indifference on climate change, disdain for women’s safety, and flirtation with culture-war theatrics, the flaw lies less with the microphone than with the script.

By the time Antony Green’s touchscreen delivered its verdict, the political landscape had not merely shifted; it had buckled. The Coalition’s once-vaunted urban backbone now belongs in a museum, alongside Menzies-era complacency and Abbott-era hubris.

Queensland delivers a shock

Queensland was meant to be Peter Dutton’s redoubt. Instead, it became his undoing. The Liberal-National leader, who had cast himself as the Coalition’s hard-nosed bulwark against modernity, was unseated by Ali France, a Labor challenger who transformed a supposedly unwinnable seat into the evening’s most startling trophy. This was not merely a loss; it was a pointed repudiation from the very voters Mr Dutton claimed to champion.

The symbolism was hard to miss. For years, Mr Dutton had railed against “elites”, mocked progressive causes, and leaned on scare campaigns that resonated in certain corners of talkback radio. But Queenslanders, it seems, can detect political decay. A 3.8% swing to Labor across the state did more than evict its most recognisable conservative; it punctured the Coalition’s narrative of Queensland as an impregnable bastion of the right.

By the time the ABC called the seat, the schadenfreude in Labor ranks was palpable. Mr Dutton, once pitched as the Coalition’s answer to Anthony Albanese, is now destined to be the answer to a trivia question about deposed opposition leaders. His legacy is a cautionary tale: confusing obstinacy with strength, and fear-mongering with leadership.

Teal Roots Run Deep:

Dutton was basically the anti-Teal candidate, and it showed. His approach to immigration and indigenous affairs didn’t so much flirt with Australia’s racist heritage as much as it bent it over the edge of a crusty mattress in a cut price, by-the-hour motel, and then smoked a cigarette with it afterward.

If the “Teal wave” of 2022 was a warning, the election of 2025 was the consolidation. The independents who took Liberal heartland seats three years ago have not only kept them; they have made themselves at home. The so-called “soft” Teal electorates have hardened. Voters have sampled life beyond the two-party duopoly and decided they prefer it.

Incumbent Teals such as Cheney, Spender and Steggall have entrenched themselves in ways the Liberals struggle to match. They are now joined in the Parliament by Nicolette Boele who won in a squeaker this time after achieving one of the largest swings in the country in the last election.

And Liberal's threw kitchen sinks at Monique Ryan in Kooyong, and yet she endures.

They are all fixtures at school fetes, climate forums and local business gatherings, not distant figures parachuted in for photo opportunities, but embedded members of the community. Their blend of social liberalism, environmental seriousness and local engagement has turned what were once symbolic wins into structural advantages.

Liberal strategists talk breezily of “winning them back”, as if a new leader and a sharper slogan will do the trick. But you cannot evict a tenant who has become part of the household. Unless the Coalition is willing to compete on integrity, climate credibility and genuine community presence, it will be renting space on the opposition benches for many years to come.

A landslide built on sand

Labor’s win in the 2025 federal election looks impressive from a distance: a commanding majority in the House of Representatives, a humbled opposition and a triumphant prime minister. Look closer and the victory rests on worryingly narrow foundations. Labor’s primary vote, at 34.6%, is the lowest ever to yield such a majority. It is the political equivalent of winning a grand final on three dubious free kicks in extra time. The Coalition did worse, securing just 31.8%. The Greens claimed 12.2%, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation 6.4%, and an unprecedented 13.1% went to “Others”, a miscellany ranging from Teal independents to protest candidates with no hope of forming government.

This fragmentation is not a statistical quirk. Since the 1980s, the combined primary vote of Australia’s two main parties has trended steadily downwards. In 1987 Labor and the Coalition together attracted nearly 93% of first preferences. This year they managed barely two-thirds. The erosion has been most dramatic in inner cities, where major-party incumbents now face credible challenges from well-organised independents, and in regional Queensland, where minor parties and populist movements command loyal niches.

In this climate, the two-party-preferred (2PP) count masks more than it reveals. Australia’s system of preferential voting allows the big parties to patch together victories by stitching preference quilts from smaller rivals. Such electoral bricolage may deliver the numbers on the floor of Parliament, but it does little to inspire. When two-thirds of voters give their first choice to someone else, it is not a ringing endorsement; it is a demand for alternatives.

Australia is not alone. Across much of the democratic world, traditional party duopolies are fraying. Britain’s Conservatives and Labour have seen their combined vote fall in most elections since the 1970s, with the Liberal Democrats, Greens and nationalist parties taking chunks of their base. In Canada, the governing Liberals and opposition Conservatives routinely face fractured parliaments, with the NDP, Bloc Québécois and Greens acting as kingmakers. New Zealand’s adoption of proportional representation in the 1990s entrenched multi-party politics, forcing Labour and National to build coalitions.

Australia’s preferential system cushions the impact of this fragmentation, allowing minority sentiment to flow back to one of the two major blocs. But the cushion is thinning. The Teal independents are no longer a one-election novelty; they are embedding themselves as durable local brands, much like Canada’s regional powerhouses or Britain’s Celtic nationalists. The Greens have shifted from a Senate nuisance to a lower-house presence, albeti reduced after Labor's inner city sweep. And minor right-wing parties, though often fractious, are stubborn in their redoubts.

Canberra’s big beasts still behave as if they inhabit a two-party ocean. In reality, they are paddling in a shrinking pool. Without genuine renewal, on policy, integrity, and local connection, Labor’s “landslide” may prove a false high tide, receding faster than either side expects. In the age of matchstick mandates, survival will belong to those who can build on rock.

When noise drowns out the message

Strip away the post-mortems and the lesson is plain: the Coalition fought an election in which it confused provocation with persuasion. Floating nuclear power “thought bubbles”, indulging in culture-war theatrics, and recycling cost-of-living platitudes may excite the faithful on Sky News After Dark, but in the metropolitan swing seats they fell flat. Voters anxious about housing, climate and health policy were offered alarm over drag-queen story hours and the suggestion, barely veiled, that a nuclear reactor might one day appear in every postcode.

Labor, by contrast, read the electorate more accurately. It campaigned on integrity in government, energy transition and women’s safety. It was territory the Coalition either ignored or derided. In the cities, voters tuned out the noise and gravitated towards something that at least resembled a plan.

Even the Coalition’s traditional media allies struggled to sweeten the verdict. News Corp editorials acknowledged own goals, disunity and a leadership brand as appealing as a parking fine. International coverage was blunter: Reuters and the Financial Times described the result as a centrist rejection of the Coalition’s drift to the hard right. Domestically, it was simpler still: voters had tired of being shouted at. In politics, as in life, once you have lost your audience, no amount of microphone will save you.

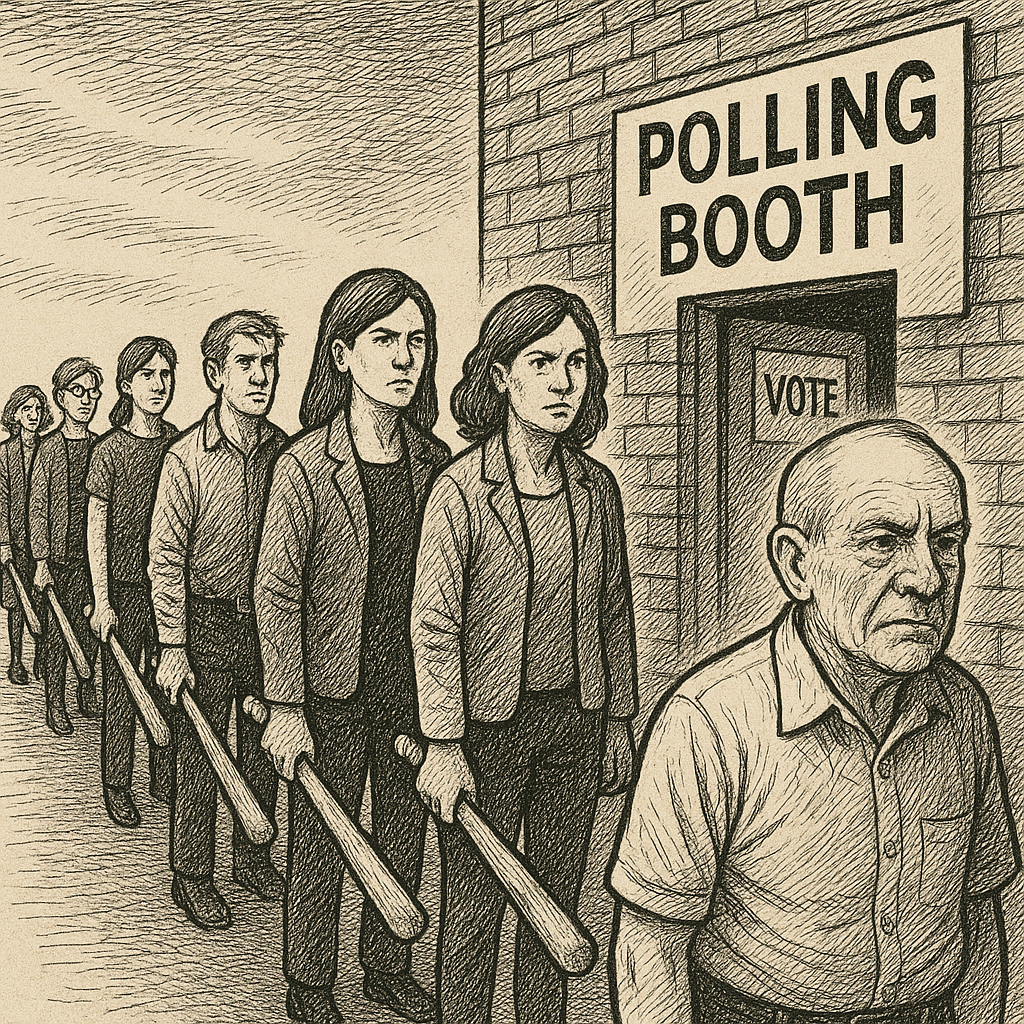

MAGA, unmade in Australia

Then of course, there was the elephant on the ballot. The Coalition’s lurch into Trumpian mimicry was as awkward as it was ill-judged. The rallies heavy on cultural provocation, the conspiratorial signalling, and the us-versus-them rhetoric may play in Mar-a-Lago; in Maroubra they looked foreign. “MAGA” politics in Australia is an acquired taste nobody asked for.

The wager was that culture-war maximalism would rally a “silent majority”. In reality, that majority was busy paying mortgages, confronting genuine cost-of-living pressures and hoping for a government that would govern. Imported grievances from across the Pacific were a distraction, not a rallying cry. Voters wanted solutions rooted in their own circumstances.

The result was instructive. Australians will tolerate much in politics, but a wholesale import of America’s political neuroses is not among them. This is still a country that prizes competence over chaos, expects leaders to behave like adults, and retains, however frayed, a belief in a fair go. The Coalition tried on a MAGA hat; the electorate handed back a dunce cap.

An eviction notice for the rightThe truth the Coalition cannot spin away is that contemporary Australia has moved on, while it clings to a political playlist from the 1990s, remixed with a few 2016 Trump riffs. Urban voters want climate action, not denial. Women seek safety and respect, not dismissive gestures. Young Australians want a housing policy, not slogans. The rest of the country would prefer competence to culture-war theatrics.

This election was more than a defeat; it was a generational eviction notice. The message from the electorate could hardly have been clearer: get relevant, or get comfortable on the opposition benches. Nostalgia is no substitute for vision, and volume no substitute for leadership. Unless the Coalition recognises the difference, its most enduring role will be leading the queue for political irrelevance.

Want to learn more? My sources are your sources: ABC, Australian Electoral Commission. The Guardian, Kevin Bonham, Anthony Green, Courier Mail, and The Australian.