By Asha Lang

Ilya Sutskever, the OpenAI pioneer, owes the world an apology. It was his 2022 NYT Mag interview with Steven Johnson that introduced the West's cognoscenti to the idea that large language models are word predictors.

The rest of us stumbled onto that article in the months after ChatGPT was let loose onto the savannah five months later. We simply took it on board and then popularised it in the cultural imagination. Like the software we were writing about, we lacked the imagination or the curiosity to dig deeper. It was an easy confection to swallow. A neat little story: the computer guesses words. How charming.

But it was not quite so. And not for the first time, the tech industry offered up a comforting tale while pocketing our awe.

The blunt truth is that LLMs are not really word predictors. At their core, AI language models are token predictors. Tiny slivers of language, chopped and diced into fragments smaller than a kindergarten sentence. Sometimes a whole word, sometimes a syllable, sometimes a lone character hanging in space. These shards are flung into the digital ferment, churned and weighted, until something like a sentence dribbles out the other side. To call it “word prediction” is like calling a jigsaw puzzle a landscape painting while you’re still rummaging for corner pieces.

Go deeper. Imagine your tender little prompt about how to politely decline a dinner invitation without causing offence. Down at the machine code level, where all poetry and politeness dissolve, your query is devoured by one of NVidia’s global warming monster-machines. There it becomes electricity flicking switches, 10011001 electricity on, electricity off, electricity off, electricity on. A dumb binary chant. Rinse and repeat until your clever little answer emerges.

Hail Calculus

The machine is not thinking. It is not pondering whether you should feign illness or claim a prior engagement. It is performing math. No candles flicker in the cathedral of silicon, unless you count the server farm air-conditioning.

So why persist with the story of word prediction? Because the industry has a knack for conflation. It tells us that a statistical trick is intelligence, that a hiccup is a “hallucination,” that selling us our own data back is progress. When a system makes a mistake, the engineers smirk and call it a hallucination, as though the machine is Kerouac on a bender, or some robot Rimbaud seeing visions.

Hallucinations are something Timothy Leary experienced when he stuck LSD tabs on his tongue. That was a trip. That was consciousness unspooled into kaleidoscope visions. What we see from AI is not hallucination but simple error. A missed calculation, a botched connection. Let’s not pretty it up.

And while we are at it, let’s retire “word prediction.” Because that phrase smuggles in another lie, one that flatters the machine. Word prediction is what the poet Allan Ginsberg did when he reached for the right adjective to make a line sing. He famously called Leary “a hero of American consciousness.” Ginsberg was not merely stringing tokens together. He was pushing at the human condition, summoning laughter, tears, the precise shiver of recognition. He wanted you to feel. He wanted you to think. Like Dylan Thomas, he wanted you to rage. He was not doing math.

To mistake one for the other is to confuse the aroma of a bakery with a photograph of bread. One is warm and alive, the other a static imitation. The machine gives us the photograph and insists it is a feast. We nod along, too dazzled to object.

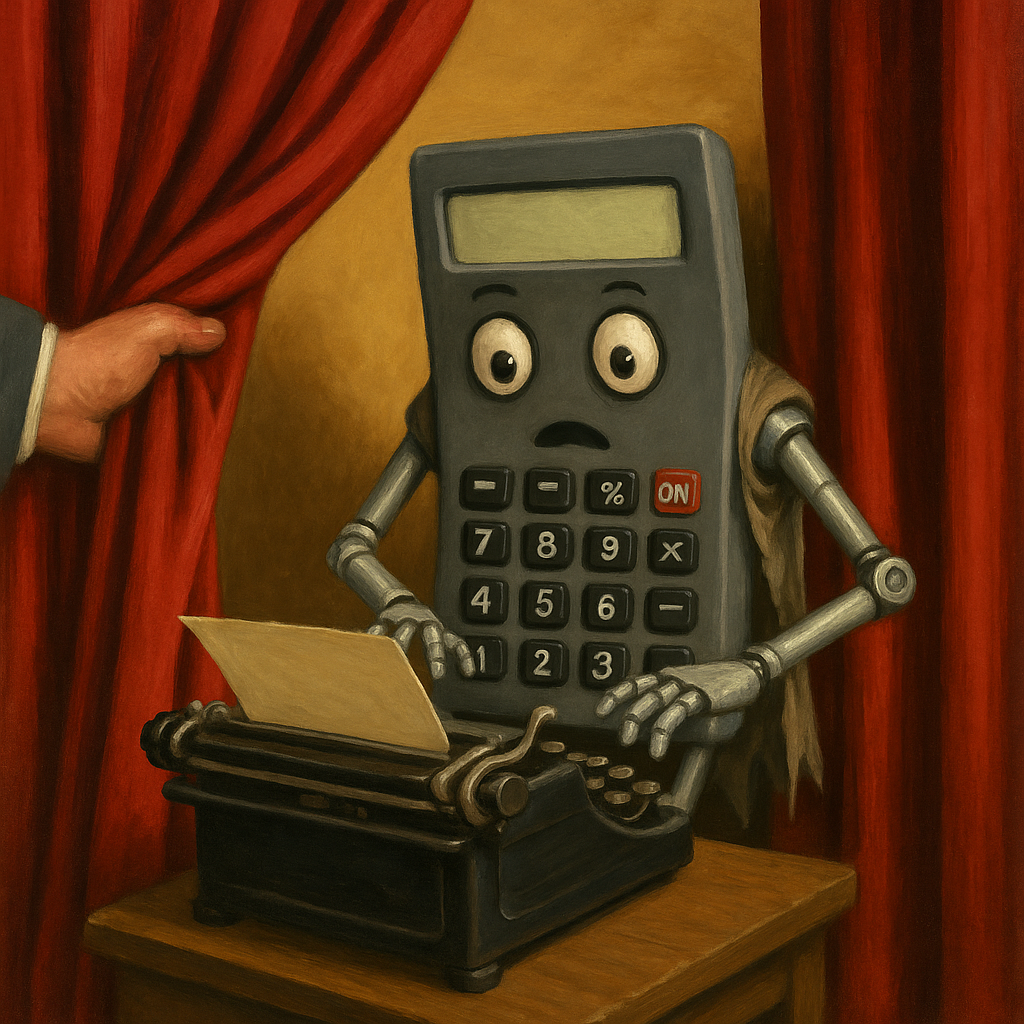

Wizard 101

This sleight of hand is not new. Tech executives have always been master magicians, pulling rabbits from GPUs while telling us we are watching history’s great turning point. We lap it up, grateful to be close enough to the spectacle to catch a tuft of fur. But we must grow sceptical. The rabbits are battery-powered, the hat is full of wires, and the magician is winking at the investors in the front row.

There is a profound intelligence at work, but it's not the machine. It’s the very clever humans who stitched the software together, or who soldered their genius into an NVIDIA chip. ChatGPT’s answers are not the noble labour of some electronic Aristotle pondering the mysteries of life. It’s wires and switches, electricity playing peek-a-boo.

Artificial intelligence? No. It’s not even a convincing facsimile. Call it what it is: pretend intelligence. A make-believe brainchild, whispered into existence by the neurodivergent ingénues working Silicon Valley’s foosball tables to generate a little bit of masculine energy, and congratulating themselves on how terribly important they are.