Leslie Carhart is not easily rattled. A veteran of industrial incident response, she has investigated intrusions into pipelines, power plants and transport systems. Yet one case required a police escort. “We’ve had to be escorted by police, by the military, in some cases, because people were blaming each other for incidents, and it had reached that point where they were afraid there was going to be violence,” says Carhart who is Technical Director, Industrial Incident Response, for Dragos, a Maryland based Cybersecurity firm.

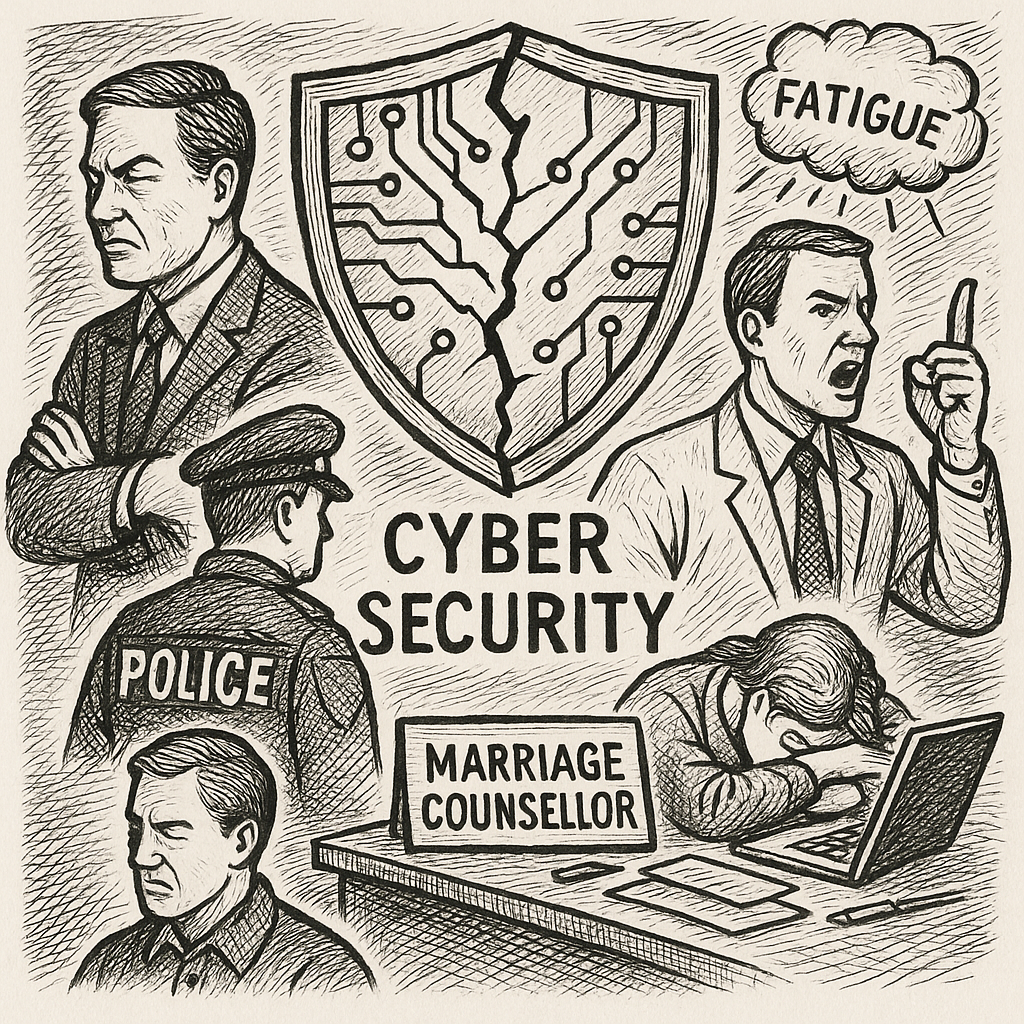

It is a telling episode. Cybersecurity is often portrayed as a contest of code: attackers deploy malware, defenders patch systems. Yet the graver breach may be human. Interpersonal distrust and exhaustion now rival technical exploits as systemic risks. Attackers need only wait while defenders sabotage themselves.

A divorce in the control room

The cultural gulf between operational technology (OT) and information technology (IT) is notorious. In factories and power plants, uptime is sacrosanct; a glitch can halt production or endanger lives. In IT, by contrast, patches and updates are routine. When IT auditors march into industrial sites with checklists, mistrust is inevitable.

“You just can’t do that in OT… What we’ve ended up with is, this tremendous hostility,” says Carhart. The divide is no trivial matter. Incident response collapses when engineers refuse to share knowledge with security staff, or vice versa. The result is a Stygian atmosphere of blame, fertile ground for adversaries who need only a moment’s distraction to slip in.

Fatigue in numbers

Beyond culture wars, burnout gnaws at the sector. Research by Omdia finds that 85% of Australian firms suffer from cyber fatigue. The toll is stark: productivity drops by three hours per worker per week; incident-response times lengthen; 17% of organisations admit fatigue contributed directly to breaches. Most troubling, nearly a third of cyber professionals are considering leaving the industry altogether.

Tim Dillon of chief analyst for the firm Omdia frames the crisis starkly: “Cyber fatigue and burnout is at higher rates today than what frontline healthcare workers experienced during covid, and that is a hell of a comment to make”. Apathy follows. “30% of cyber people, cyber professionals, are saying, I’m not moving company and doing cyber, I’m changing my career”.

The soft whispering of disengagement, staff ceasing to care whether breaches occur, may prove more dangerous than foreign adversaries or cybercrime syndicates. Unlike servers or code, skilled human judgement cannot be spun up in the cloud. Its erosion is as slow and relentless as a glacier under warming seas, yet far harder to reverse.

And the problem of cyber burnout may be about to get much worse, fast, with the rise of agentic AI.

Technology introduces fresh vulnerabilities. Tom Skully, Director & Principal Architect for Public Sector, Palo Alto Networks warns that firms are rushing into agentic AI systems that do not merely analyse but act, booking tickets, scanning code or summarising emails. Nikesh Arora, the firm’s boss, says it is like giving artificial intelligence “arms and legs”.

The problem, Skully notes, is that “the reality of that is, they like to click links”. Bots, like humans, will err. Deployed en masse, they risk becoming an octopus of unsupervised agents, their tentacles wrapped around corporate systems, multiplying mistakes at machine speed. Already, three-quarters of firms report incidents tied to generative AI, often stemming from “shadow AI”: employees using personal devices to access public models because corporate provision lags.

Palimpsests of complexity

Even firms that avoid shadow AI stumble over complexity. Netskope, a cloud-security vendor, notes that enterprises typically juggle 68 different security tools. This palimpsest of overlapping platforms creates blind spots and overwhelms staff. Tony Burnside, its Asia-Pacific head, puts it plainly: “Complexity is absolutely the enemy of security”. His firm pitches a single integrated platform as the cure, with Australian government agencies and banks among its customers.

Simplification is not merely a vendor’s sales pitch. Over-complexity paralyses decision-making, just as surely as OT-IT mistrust or staff burnout. Whether the problem is an overworked analyst, a quarrelling control room or an octopus of bots, the system fails not because adversaries are omnipotent but because defenders are divided.

A regulatory squeeze

Boards are belatedly alert. Directors are now personally liable for cyber failures. Yet expectations remain detached from reality. Most executives expect recovery from a breach within five days; in practice, the average is 30 to 42. Regulations proliferate: one bank faced more than 3,000 separate cyber and governance requirements. The burden risks deepening fatigue without delivering resilience.

Carhart cautions against Hollywood caricatures. Attacks on industrial systems rarely cause instant explosions. More often they disable monitoring screens, delay logistics or quietly exfiltrate secrets. State groups in Russia, China and Iran have proved adept; ransomware gangs are following suit. The barrier to entry is falling, even as defenders grapple with ageing equipment and ossified culture. Many critical systems still run on Windows 95 or NT, with life cycles measured in decades.

The real lesson is sobering: the system is more fragile than the technology. Cybersecurity is not merely about malware signatures or compliance checklists. It is about ensuring that the people charged with defending critical systems can trust one another, endure the strain, and make decisions amid uncertainty.

The human firewall

For C-suites, three imperatives stand out. First, rebuild trust: without cultural integration between operational technology and information technology, incident rooms resemble divorce courts. Second, address fatigue: mental health, realistic expectations and career pathways matter as much as technical skills. Third, simplify: the fewer moving parts, the fewer cracks adversaries can exploit.

Failure to act leaves firms vulnerable to the silent breach, one that requires no exotic exploit. It arises when defenders are too tired to notice, or too hostile to co-operate.

Carhart understands this better than most. Her career has been spent among oil rigs, power stations and water plants. Yet her most important tool is not a malware scanner but diplomacy. That is why the sign on her desk does not read “Incident Responder”. It reads: “Marriage counselor.”